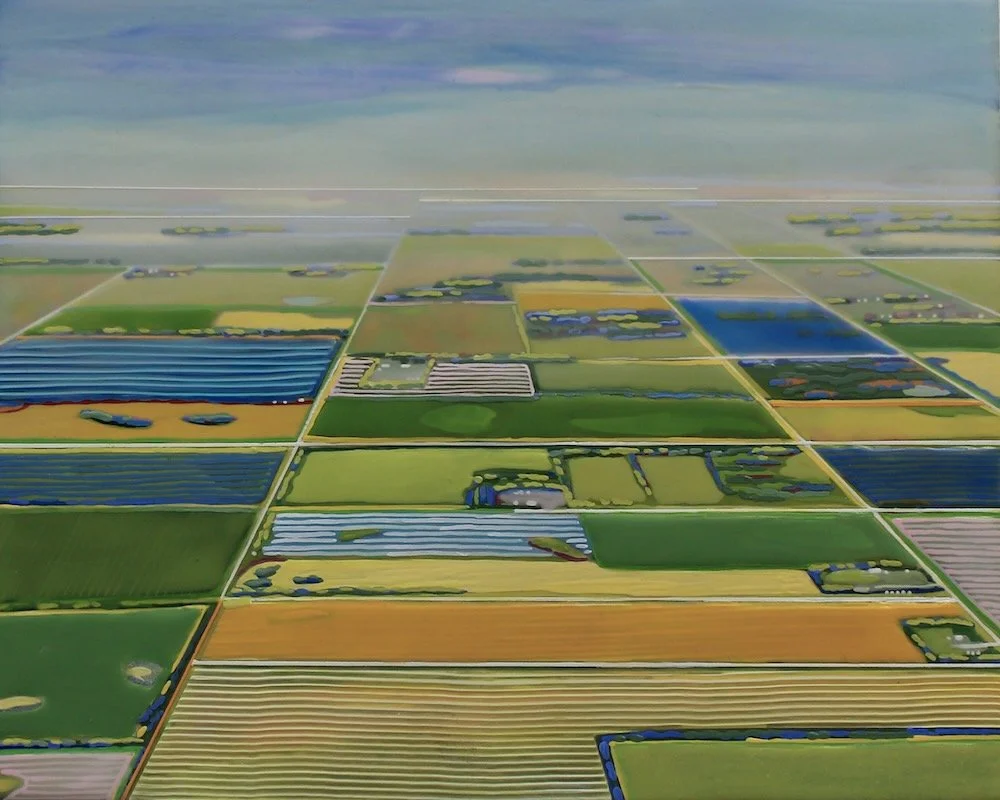

Viewfinder, Grasslands

Acrylic/Panel 2024

“When I was a kid living in the city. I didn’t realize what a windy place Saskatchewan is, when you live someplace where there’s nothing to blocking. You really notice it all the time. It makes a huge difference on the moisture, especially after a drought when all the litter is reduced. Because the litter acts like a, like a windsock on the microphone, it really buffers the wind speed right over the ground and makes a big difference in how much moisture you lose...so we had all these consecutive drought years, compromised litter levels, and then the wind makes a big difference faster than it would if a litter was still there.”

Krista Ellingson, MSc Pag (Val Marie Pasture Survey; Monet Pasture Survey)

Natural Area Manager - Working Landscapes | Nature Conservancy of Canada

Viewfinder, One of Clint’s Favourite Views I

Acrylic/Panel 2025

Viewfinder, One of Clint’s Favourite Views II

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“...Basically, as far as I can see grass this way, as far as you can see it that way, it’s pasture. It’s kind of a pretty neat piece of land ...we do use horses in the real rough country, not saying it’s better than somebody uses a bike on their own places or whatever it is, but it is something we do here that’s fairly environmentally friendly. It’s very un-invasive to the land, right. I don’t leave track because I don’t spread weed seed... It’s a very natural way to travel. Animals really don’t look at you much cause when you’re on a horse you are part of nature. And you know it is part of the heritage too... but it is a management tool.”

Clint Christianson (Beaver Valley) Pasture Manager Beaver Valley Grazing Corp& Val Marie Grazing Corp

Viewfinder, Half Empty, Half Full

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“Well, I think the Aspen Parkland is really one of our last great chances on the prairie to be saving some habitat for some species. A lot of them are very common, abundant birds, and insects, mammals. But we're not really monitoring the common species anymore because we spent so much attention on rare ones, the endangered ones. And that a more serious sign of ecological decline is when super abundant species start to slide...”

Trevor Herriot (Cherry Lake), Writer & Naturalist

Viewfinder, Boundaries

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“We’re looking for the amount of layers, when your vertical layers have a tall canopy trees & you have a shorter tree species or high bush tree species, and then you can go to your lower layer... the more different layers that you can see is more variety... But you also look at your layers across the horizontal landscape as well. So, if you look from here to the meadow and those little different ecosystems...you don’t want it all to be different layers. You want little areas that have heavy grazed, because different animals need you know shorter grass...but then you have a shrubby area because they nest in the shrubs or they need a lot of litter to build their nest in. So having that variety across the land horizontally as well as vertically as what we’re looking for.”

Marla Anderson Barlow (Elizabeth Hubbard Property walk) B.Sc. Stewardship Coordinator – SE | Nature Conservancy of Canada

Viewfinder, Stand of Trees

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“You know culture is to be lived in the moment. It’s not lived in the past. It’s not lived in the future. It’s lived right here in the moment. Being present and living that sort of cyclical lifestyle every year. To be on the land, to be harvesting, to be interacting with it, right. And that’s why I think food sovereignty and food cultures is so important, vital to the survival of a language and identity for indigenous peoples.”

Philip Brass (Elizabeth Hubbard Property walk), Land-based educator at Piapot First Nation

Viewfinder, Kinnikinnick

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“Bear Berry or Kinnikinnick in nêhiyawêwin cree. And that's, one of the main foundational ingredients for making our pipe tobacco. I usually mix that with a blend of, with red willow and usually harvest the red willow in the wintertime. When you can see it turns bright red, usually like February. Then you peel the red bark off, and underneath there's a clear membrane, another layer of skin. You peel that, dry that. Then once that's crumbled up, mix that with these. And, of course, you can add other things to your mix. But those are the two foundational ingredients.”

Philip Brass (Elizabeth Hubbard Property walk), Land-based educator at Piapot First Nation

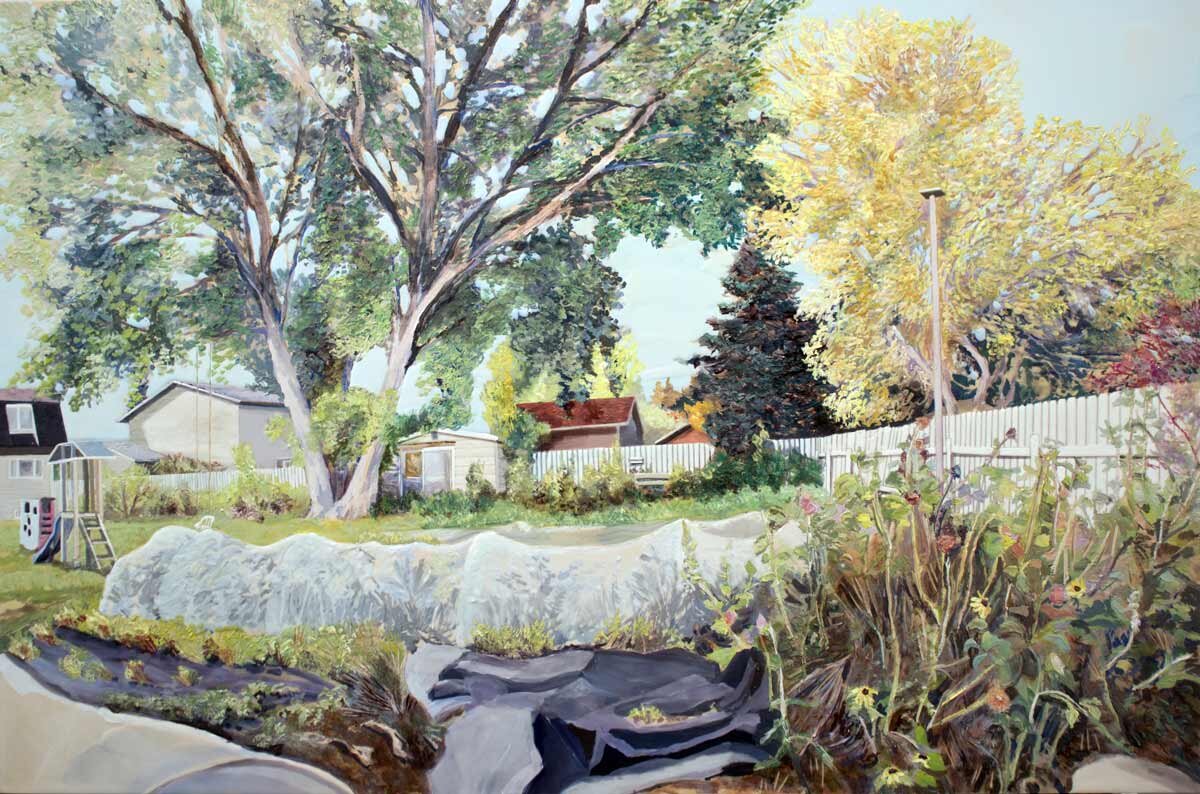

Viewfinder, Hunting Patch

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“I started coming here in 1976, and, I came here to hunt. There's really good deer population and lots of ruffed grouse and there was the commune, my friends. And as I came here, every time I came up, there would be another piece of land bulldozed. And so, when Dane offered me, this piece of land, and he offered it to me at a price I couldn't refuse. So- I didn't. I bought this land so that it wouldn't get bulldozed.”

Jamie Russell, Artist, Hunter (Thickwood Hills Property/Spiritwood)

Viewfinder, In Memory of Giles Lalonde 1950-2025, Tree Planter, Citizen Scientist

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“So that's, that's the aim is to really have a mixed wood in here, both in terms of like the big trees but also the understory. That might take 30 or 40 years or 50 years before you can actually make a judgment in terms of what kind of understory you've got.” — Giles Lalonde

“And there's also the question of like, what are we trying to restore to? We don't know what was here before, but we know what's similar nearby.” — Sara Bradley

In Memory of Giles Lalonde 1950-2025, Tree Planter, Citizen Scientist

Viewfinder, Boggy Creek

Acrylic/Panel 2025

On the donation by Barbara & Doug Mader of their property to the Nature Conservancy of Canada: “It’s a piece of pasture, 40 acres, near Lumsden...he (Doug Mader) thought it would be lovely to have this piece because Boggy Creek runs through it... I asked myself what are we saving things for... I started to think about my background in an agricultural family...and think about those fields. The one item that really hit me was going back to the farm and there was no road allowance...I can’t return it, if I can find a way to make some reparation for what I could see happening in my own family farm. I don’t think of it as bold...I think of it as determined, earnest... I just saw a clear path and was determined to get on it. I feel right about it, this fits with my beliefs with who I am... because were we good at saving”.

Barbara Mader Artist/Philanthropist

Viewfinder, Walking with Phil & Kay, Thickwood Hills’

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“The one school, one farm program develops partnerships between rural landowners and schools. And, the idea is to give students an opportunity to be out on the land and learn about the native plants that would normally grow in Saskatchewan ecosystems, whether it's prairie down south or aspen, parkland or up here. We're in the boreal transition zone.”

Kay & Phil Willson Environmental Educators

Viewfinder, Close Up Spruce Planting

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“So out in this area you can see like this had been a field. And just over the last, say, 18 years or 20 years since there hasn't been, a crop put in, snowberry is coming back. And wild rose is coming back and campylium is coming back and, the willows are coming back. And, so a lot of the natural regeneration here is adding to the biodiversity. And the spruce are our attempt to help recreate a mixed wood forest because it's my understanding that Thickwood Hills traditionally had a mixed wood.”

Kay Willson Environmental Educator

Viewfinder, Mistawasis Nêhiyawak

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“Mistawasis, like many First Nations have what's called land-based learning that we've integrated with our classroom based learning at both of our schools. Where, the kids spend time on the land, learning from the land, learning about the land and integrate that with different subjects that they’re taught in the classroom.”

Anthony Blair Dreaver Johnston, Special Advisor, Mistawasis Nêhiyawak

Matthew Braun (Mistawasis walk) Program Director – Working Landscapes | Nature Conservancy of Canada

Viewfinder, Mistawasis Nêhiyawak Pasture

Acrylic/Panel 2025

“We want our community as a whole to realize that, despite there not being buffalo here, we still have a connection. And so that's partly why we need buffalo on our land, just to remind ourselves of our ancestral connection to buffalo.”

Anthony Blair Dreaver Johnston, Special Advisor, Mistawasis Nêhiyawak

Matthew Braun (Mistawasis walk) Program Director – Working Landscapes | Nature Conservancy of Canada

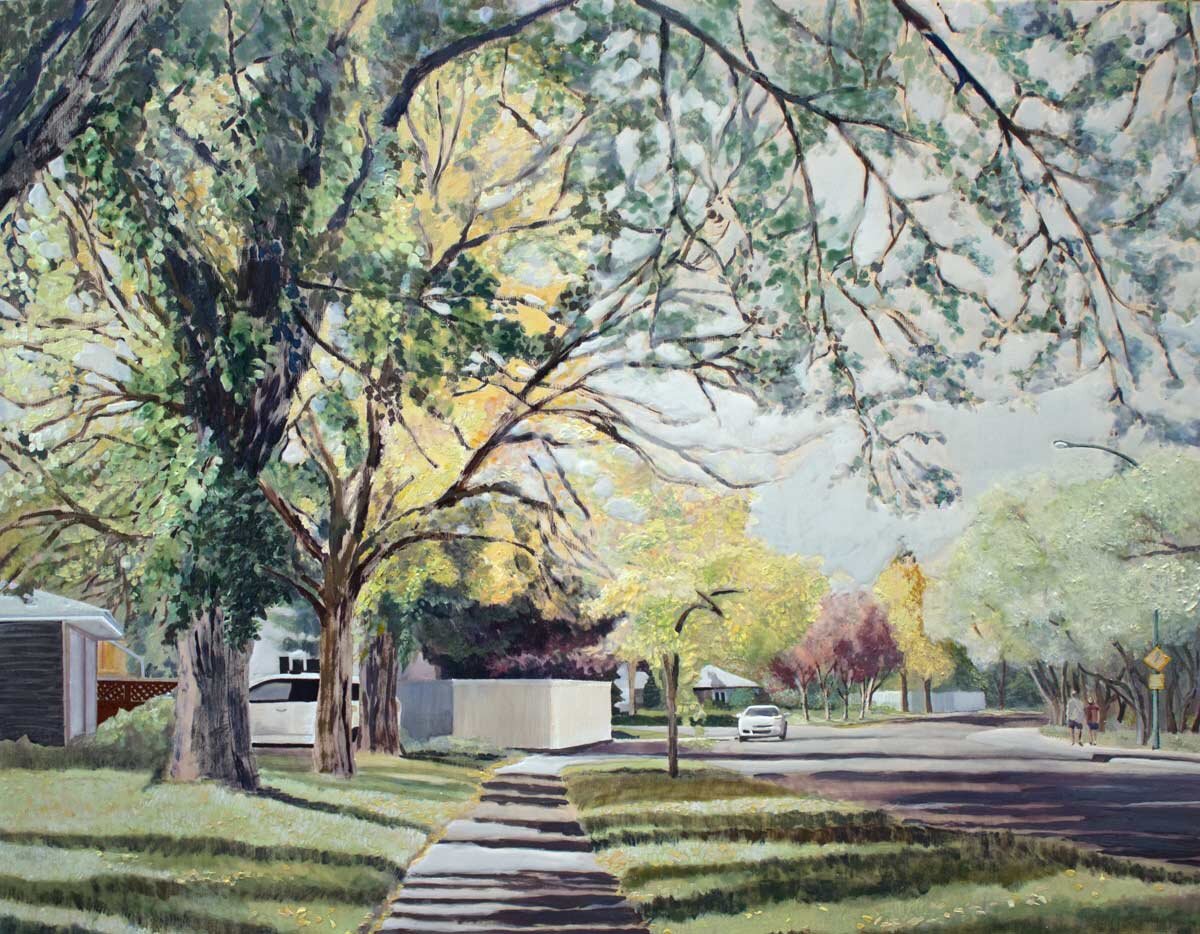

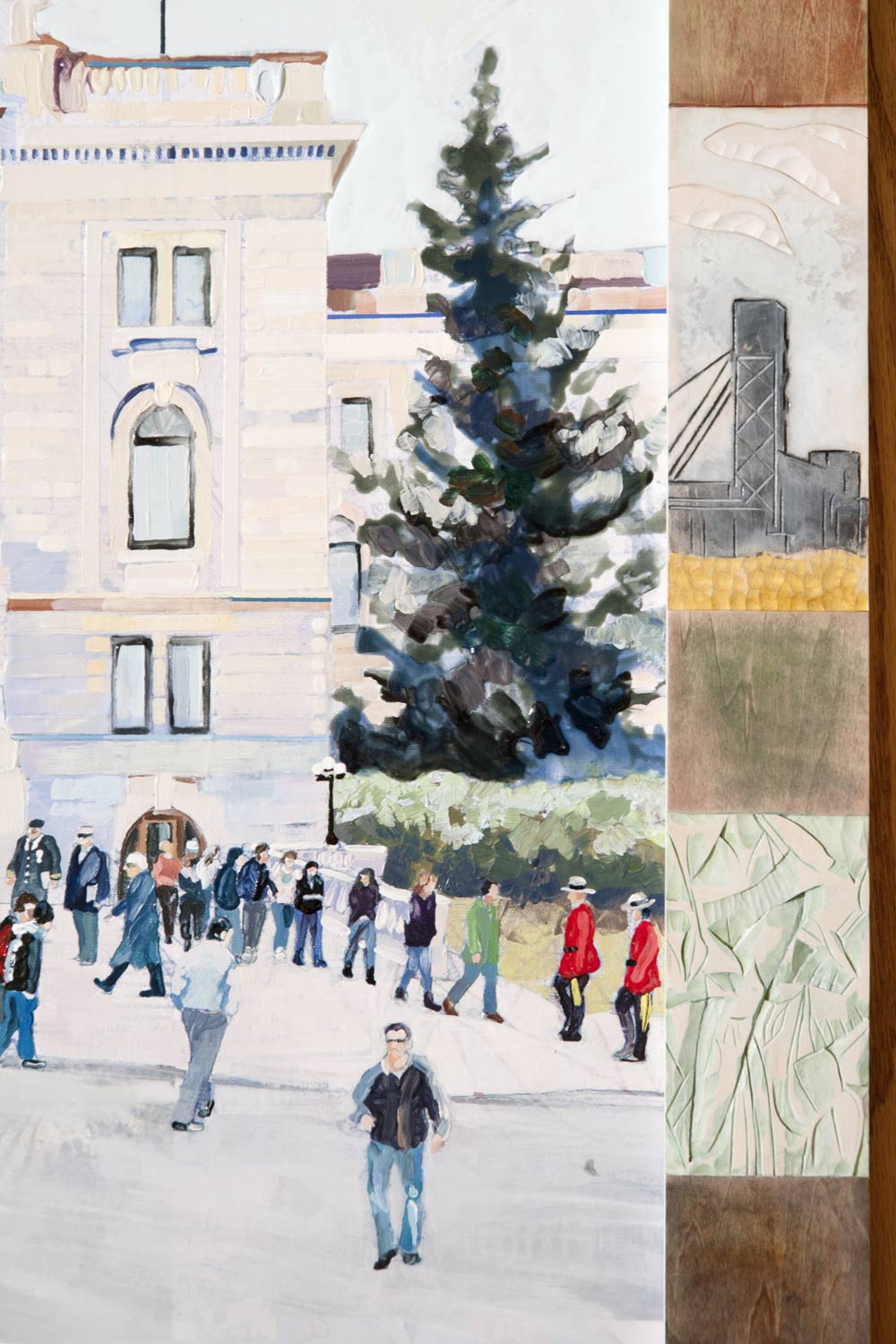

Landscape painting in Canada has frequently been dominated by work less rooted in human geography; exploring the wilderness and generally downplaying the human reconstruction of the western prairies. John Prine was whispering in my ear as I started the dashcam series, placing the roadway firmly in the center of these artworks. Casting the viewer as the main character in a journey through the landscape altered by but not contained by human intervention. The works vary in size, exploring how shifting scale contributes to the visual impact. All the works feature acrylic paint layered on panel.

The series uses multiple layers of paint, often combined with carving and sanding, reworking the surface, literally reconstructing the landscape. I hope that this process of building up the surface of the artwork translates into how people experience the paintings, as the layers and shifts in the surface texture slowly are revealed over a longer period of contemplation. As the work progressed, I started to remove certain elements concentrating on placing the carefully delineated structure of the roads and signage in contrast with the loose dense painting of the landscape. Emulating some of the inherent contradictions in human interaction with our environment.

I strive for these works to be emotive paintings, rooted in physical journey but trying to build on the poetic nature of simple life experience. Geography as metaphor, with the acknowledged influence of the many writers, musicians and artists who have explored the rich terrain of our passage through the landscape.

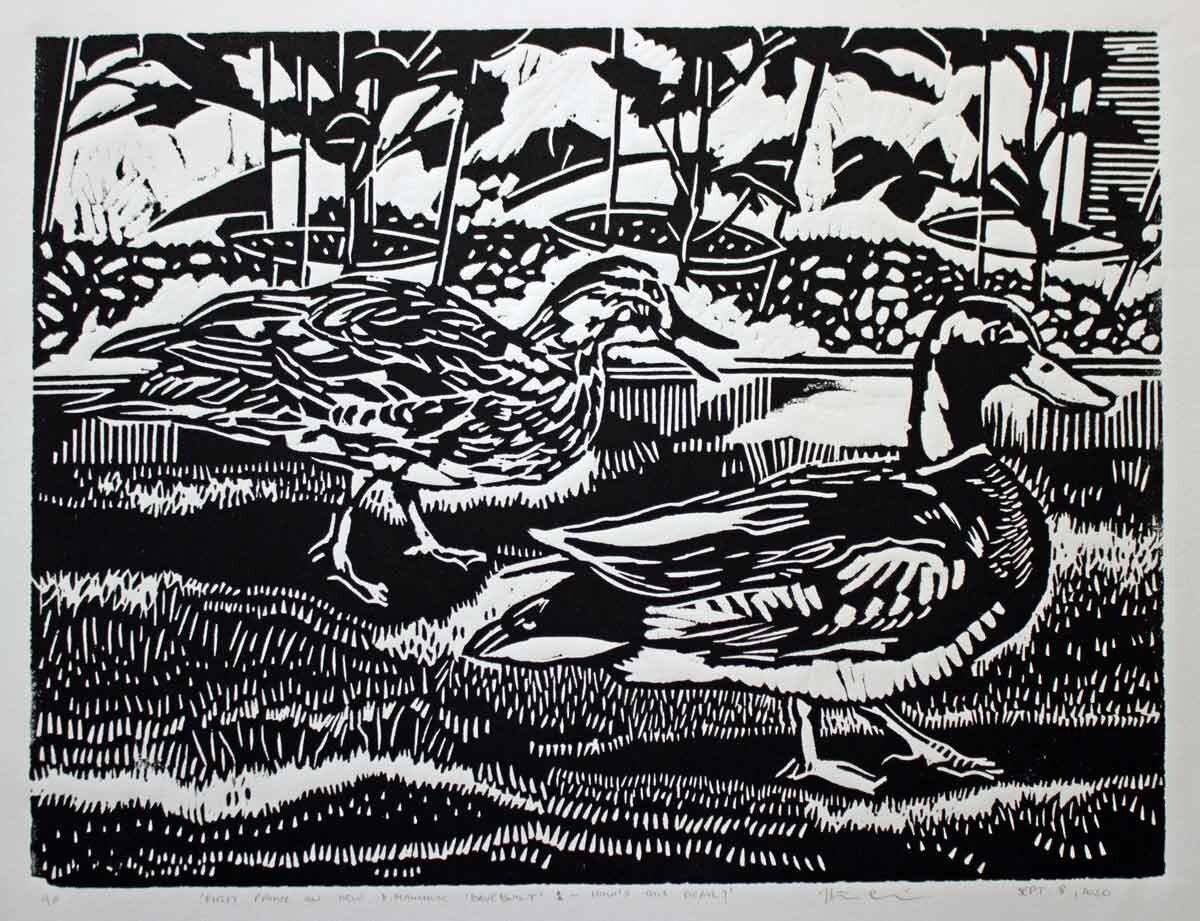

And then in the spring of 2020 journeys suddenly became infrequent, as we all grappled with the necessary changes created by the COVID 19 pandemic. As the weeks of reduced city traffic continued, I started to observe changes in my environment. Local wildlife started to openly dominate my surroundings, brazenly travelling the local roadways and freely carousing throughout the neighbourhood. I started to ponder the importance of animals as portents in classic stories, religion and literature. The result is a body of work entitled Neighbours.

This is a series of block-prints that feature the animal visitors that I observed from my studio. It is a playful attempt to cast the animals in the role of portents, the imagery is simple and generally open ended. The work was created in the context of our current situation of a world-wide pandemic and on-going environmental crisis. I believe that the animals provide a moment of hope and perhaps wisdom in their ready adaptation and celebration of freedom in the midst of human crisis. Their behavior, perhaps, showing us all a pathway forward.